Ever found yourself wondering how tall people actually are in Korea? You’re not alone. Lately, I’ve been noticing this odd spike in curiosity—especially from friends in the U.S.—about the average height in Korea, and to be honest, I get it. With the global rise of K-pop idols, Olympic athletes, and Korean dramas that somehow make everyone look like they walked off a runway… yeah, the question sneaks in: Are Koreans really that tall now?

Well, here’s the thing—height isn’t just about looks. It’s tied to nutrition, public health, even national development. And when you start comparing numbers—Korean male height vs. U.S. averages, or global height rankings—you’ll see a story unfolding that goes way beyond centimeters on a chart.

So let’s dig into the data, the trends, and yep, even a few myths you’ve probably heard along the way…

What Is the Average Height of Korean People Today?

You’d be surprised how often this question comes up—especially from folks curious about K-pop idols or Korean athletes. So let’s clear it up with some solid numbers. As of 2025, based on the latest figures from South Korea’s Ministry of Health, the average height for Korean men is about 174.5 cm (5’8.7″), while Korean women average around 161.3 cm (5’3.5″).

Now, here’s what I found interesting: these numbers aren’t flat across the board. Younger adults (say, early 20s) are noticeably taller than older generations. You’ll also see slight differences depending on whether someone grew up in Seoul versus, let’s say, a rural town in Gangwon Province. Urban environments tend to offer better nutrition and healthcare—two things that quietly shape national height trends over time.

Here’s a quick side-by-side I put together for easy comparison:

| Group | Average Height (cm) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Korean Men | 174.5 cm | Younger men trend closer to 176 cm |

| Korean Women | 161.3 cm | Height has steadily increased |

| Urban Adults | +1.5 to 2 cm above | Better access to health resources |

| Rural Adults | Slightly below avg | Gap narrowing slowly |

What I’ve noticed is that Korea’s upward height trend mirrors what happened in the U.S. decades ago—growth tied to rising income, better diet, and health awareness. But is Korea catching up to U.S. averages? Well… not quite yet. But that’s a whole other rabbit hole we’ll get into next.

How Does Korean Height Compare to Americans?

Now, here’s something you’ve probably noticed without even looking at a chart—Americans, on average, are still taller than Koreans, but the gap isn’t as wide as you might think. I used to assume the difference was massive (blame the NBA and Hollywood), but when I actually dug into the numbers? Totally different story.

According to the U.S. CDC and Korea’s Ministry of Health (yep, real government data, not gossip from a Reddit thread):

- Average U.S. male height: 177.6 cm (5’10”)

- Average Korean male height: 174.5 cm (5’8.7″)

- Average U.S. female height: 163.5 cm (5’4.4″)

- Average Korean female height: 161.3 cm (5’3.5″)

So yeah, there’s a difference, but it’s about 2–3 cm on average, not a whole head taller like some people imagine. That said, culturally, it feels more significant—especially because American media tends to idolize height in sports, fashion, and even politics (don’t get me started on that).

What I’ve found interesting:

- In the U.S., height often signals athleticism (think NBA, NFL), confidence, even leadership (weird, I know).

- In Korea, height’s linked more to aesthetics—clean silhouettes, modeling standards, K-pop stage presence.

- Teens in both countries are getting taller, but nutrition and genetics play different roles depending on region and lifestyle.

Factors Influencing Height in Korea

You probably already sense height isn’t just genes—it’s a mixture of habits, policy, and plain luck. What I’ve found is that small everyday choices (and big public programs) stack up over decades. In Korea you’ll notice several clear drivers:

- Nutrition (Korean diet & school meals): Improved protein and calcium intake through school lunches and wider food access boosts childhood growth—I’ve seen kids gain an edge after consistent dairy and fish in their diet.

- Healthcare & public health: Better vaccination, prenatal care, and growth monitoring mean fewer stunted kids; you benefit when systems catch problems early.

- Family genetics: Your parents set a baseline, but they’re not destiny—environment shifts the outcome.

- Exercise habits: Weight-bearing activity in childhood (sports at school, hanwoo? kidding) helps bone density and stature potential.

- Socioeconomic factors & lifestyle changes: Urban diets, less manual labor, globalized foods—all reshape growth patterns.

Now, here’s the takeaway I give friends: focus on childhood nutrition and movement—those are the biggest levers you actually control.

The Role of Height in Korean Society

If you’ve ever watched a K-drama and thought, “Wait… is everyone in Korea tall and model-tier gorgeous?”—you’re not alone. Height plays a surprisingly loud role in Korean society, and honestly, the pressure is real.

What I’ve seen (and heard from Korean friends) is that height isn’t just a physical trait—it’s a social asset. Here’s how it shows up:

- Dating expectations: You’ll hear things like “180cm oppa” tossed around in conversations or bios—ideal Korean male height is practically its own dating filter.

- Career bias: In corporate settings, especially for men, taller individuals are often viewed as more “capable” or “authoritative.” You might not like it, but it happens.

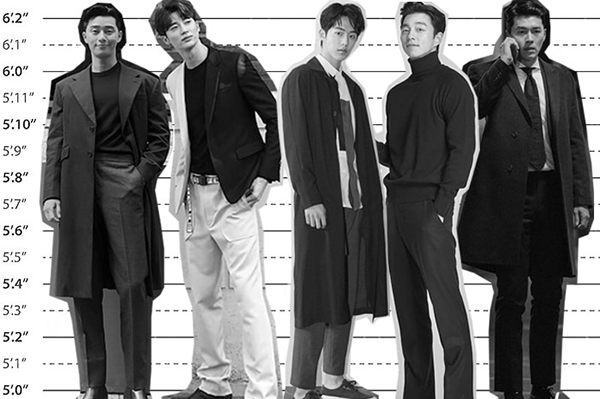

- Pop culture influence: K-pop idols, actors, even influencers tend to be on the taller side. Think BTS, Cha Eun-woo, or Lisa from BLACKPINK. They’ve set the tone, whether intentionally or not.

- Beauty standards: Combine height with fair skin and a V-line jaw and—boom—you’ve got the “ideal look.” No pressure, right?

- Compared to the U.S.: It’s a bit different. In the U.S., being tall helps in modeling or basketball, sure—but it’s not as tightly baked into everyday social value.

Is Height Increasing in Korea Over Time?

If you look at the numbers, you’ll see something pretty remarkable—Koreans have grown taller faster than almost any other population in the last 50 years. I remember stumbling across an old World Health Organization chart and doing a double take. In the 1970s, the average Korean man stood around 167 cm (about 5’6″). Today, that number’s closer to 174.5 cm. That’s nearly an 8 cm jump in just two generations.

Why the surge? You can trace it back to a mix of nutrition, public health, and plain old progress:

- Post-war recovery & nutrition: After the 1950s, improved diets—especially more protein and calcium intake—became a national priority.

- Government health programs: Regular school checkups, milk programs, and better prenatal care all pushed growth rates upward.

- Socioeconomic changes: Urbanization meant better food access and healthcare, closing the gap between city and rural kids.

- Global influence: Western diets (and ideals) quietly shifted local eating patterns and height expectations.

What I’ve found fascinating is how Korea’s height growth curve now mirrors the U.S. trend from the mid-20th century—but with one key difference: it happened twice as fast. You can literally see the nation’s development written in centimeters.

Height Myths: Korean Stereotypes vs. Reality

Alright, let’s just say it—you’ve probably heard someone say “Koreans are short,” right? I used to think the same, mostly because growing up in the U.S., the only exposure a lot of us had to Korean height came through old stereotypes, anime caricatures (yes, wrong country, I know), or exaggerated media. But here’s the thing: those assumptions just don’t hold up anymore.

Take a look at this side-by-side, and you’ll see what I mean:

| Group | Perception (Media/Myth) | Reality (2025 Data) |

|---|---|---|

| Korean Men | 5’6” or shorter | 174.5 cm (5’8.7”) |

| Korean Women | 5’1” or 5’2” | 161.3 cm (5’3.5”) |

| American Men (for contrast) | 6’0″ (often exaggerated) | 177.6 cm (5’10”) |

| American Women | 5’6” | 163.5 cm (5’4.4”) |

What I’ve found is that most of the gap is mental, not physical. American media tends to idealize “tall” in a way that distorts what average really looks like. K-pop stars, for example, aren’t short—they’re actually taller than you’d expect, especially compared to global averages.

So next time someone drops the “Koreans are short” line? You can politely (or not-so-politely, depending on the mood) bust that myth with real numbers. Because data > outdated bias—every single time.

Related post: